Mamdani on October 7th

Why Campaign Strategists Read These Moments Differently

A candidate’s statement can read one way to activists and another to those of us who think in terms of votes. Zohran Mamdani’s message on the anniversary of the Hamas attacks illustrates the split.

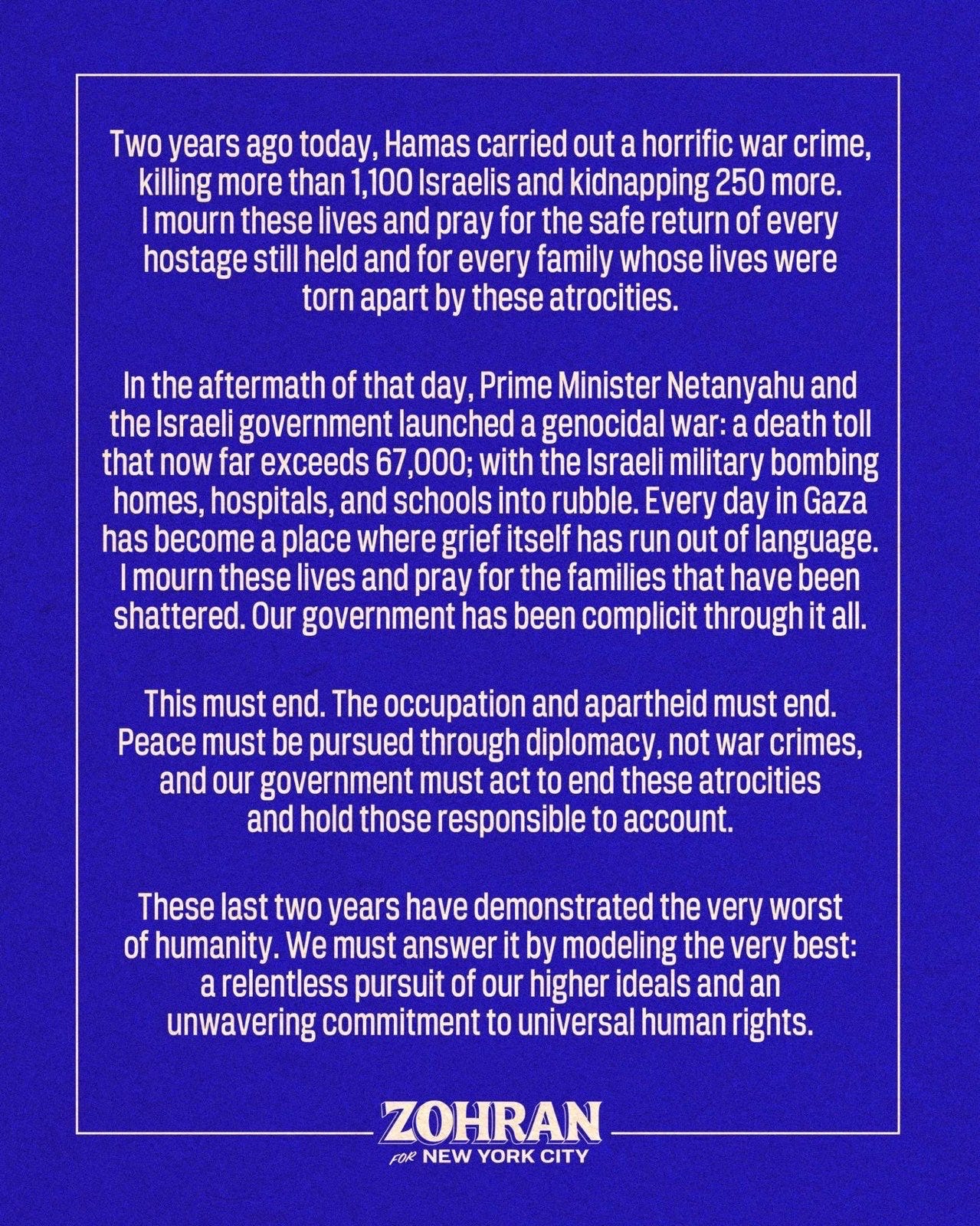

His statement named Hamas’s October 7 attack a “horrific war crime,” mourned Israeli victims, but also called Israel’s response “genocidal,” placed blame on Netanyahu and the Israeli government, and demanded an end to occupation and apartheid. For campaign strategist working retail politics, that looks like a calculated balance: enough moral clarity to signal distance from the old Democratic consensus on Israel, but still positioned for a general election in a city where some Jewish voters, older Democrats, and many centrists remain sensitive to perceived anti-Israel framing.

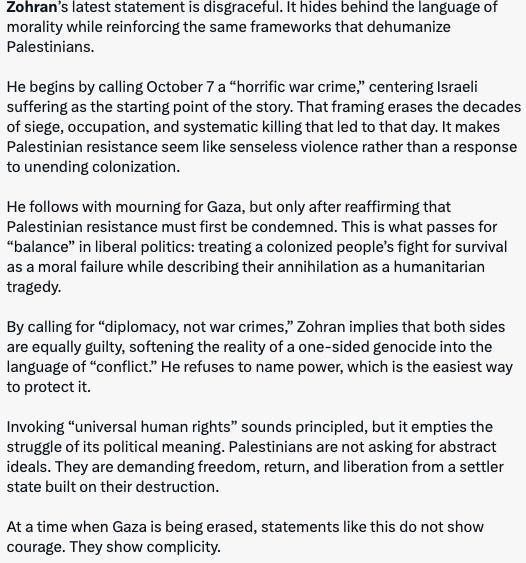

Activist networks judged it harshly — not because it lacked substance, but because it used the wrong starting point and failed to cast Palestinian resistance explicitly as legitimate. That is a critique emerging from a different logic: vanguard politics. Movements seek to define the horizon of justice and consciousness; campaigns seek to assemble majorities under existing conditions.

For those of us who do campaigns, the “median voter” is a cold but unavoidable anchor. Polling shows Democrats moving left on Israel–Palestine, especially younger voters, but the median New York Democrat (and certainly the median general election voter!) is not yet aligned with the maximalist movement position. Calling Hamas’s actions terrorism remains widely expected; describing Israel’s war as “genocide” pushes the envelope, but now polls as acceptable among much of the Democratic base. Going further, such as erasing Israeli civilian suffering or endorsing armed resistance, would likely trigger backlash large enough to lose viability.

Marxist theory has long-drawn the line between vanguard and mass politics. Vanguard movements agitate, raise consciousness, and are free to speak in uncompromising terms because their objective is ideological transformation. Mass parties, especially within liberal democracies, survive by building hegemony — weaving together disparate blocs under language that feels safe to a majority. Mamdani’s task is not to be the vanguard, but to translate its energy into an electoral form that can govern.

Strategically, this is how discursive boundaries shift. Candidates test new language — here, using “genocide” — but maintain a bridge to the electorate. Activists read this as compromise, while strategists interpret it as a careful attempt to expand what voters will accept.

The tension is expected; it is part of how ideas move from protest into electoral politics. For those of us working campaigns, the sequence is clear: first shift what ordinary voters can hear, then build the coalition to act on it.